The Small Bow is funded entirely through paying subscribers. We use your money to help pay for all our freelancers and Edith’s illustrations. Our newsletter is for people who have substance misuse issues or struggle with mental health, but our stories have a far greater reach than that. TSB is for the unlucky and the unlovable. The ugly and the lost. The super lonely and the swiftly abandoned. It’s whatever you need it to be.

If our newsletter has helped you feel less wicked, less shitty, or less afraid, then please consider financially supporting us. Subscribers get access to the entire archive, the Sunday essay, the entire recommendations roundup, and the complete rundown of my weekly recovery program. Seriously—thank you for letting us be of service.

I've finally gotten back into a regular BJJ routine after an 11-month hiatus recovering from minor knee surgery. Physically, I’m fine. It’s a demanding sport, and I’m middle-aged and small, so the chance of my body getting wrecked is higher than most, so I might as well use what I have while I have it. But I'm not anywhere close to mentally back yet. I have similar nerves and anxieties that I had early on, primarily because when I've been gone, most of the guys I trained with are so much better than me now (as they should be). Still, it's mostly because I'm working with all the new people. It's that first-day-of-school feeling all over again, and the reality is that most of these people can and will beat you up. But it's an incredible way to work through all those primal, annoying, leftover childhood fears. What else is there to do in this life? Gotta keep subtracting useless stuff.

I'm on vacation this week and plan not to work that much, so instead, I'm serving you with a remixed essay from last year about entering a BJJ tournament. (It was almost one year to the day.)

Underneath that is the gratitude list, poem, quotes, and recommendations—the usual Sunday fare. See you down there!

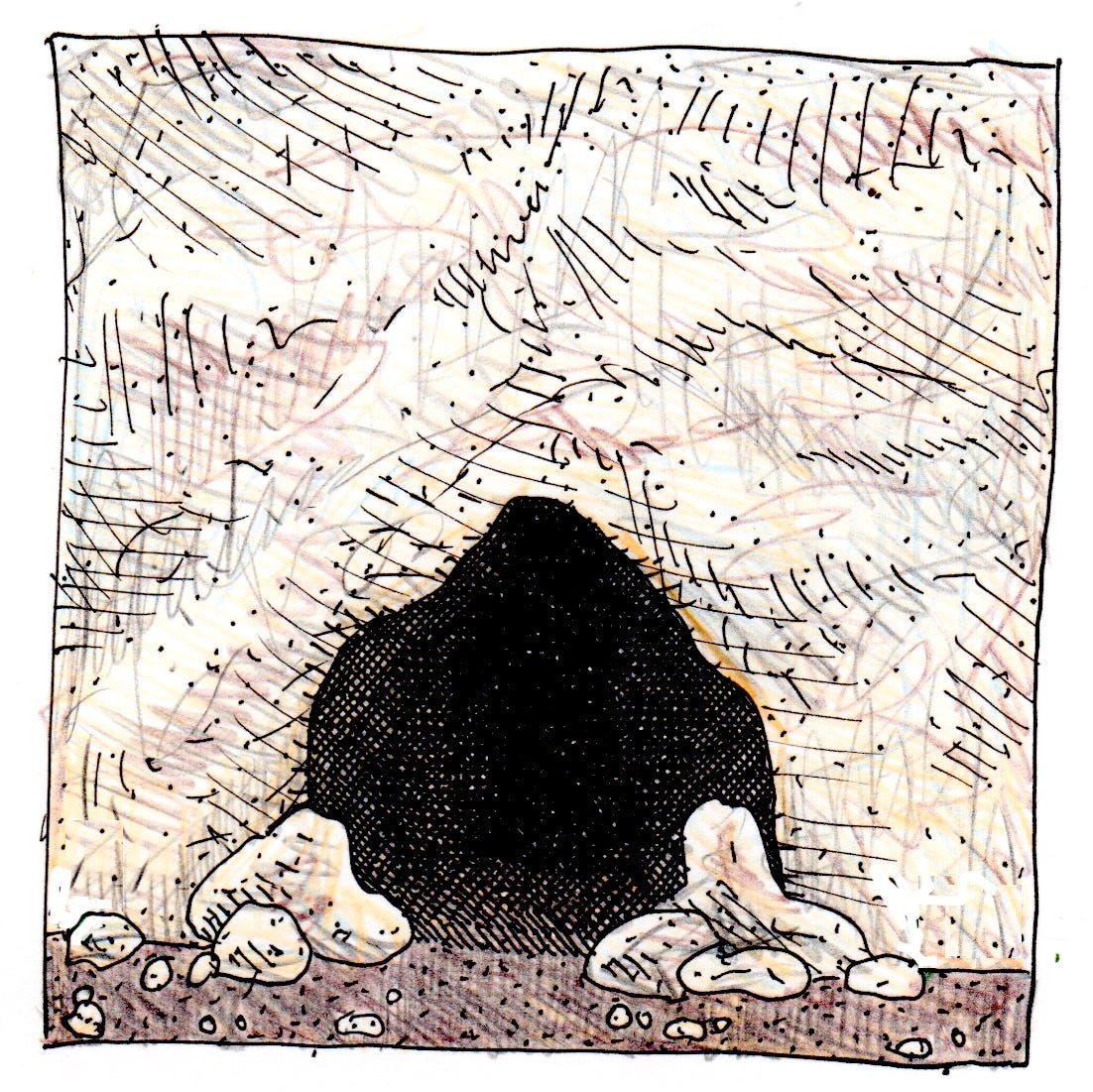

THE CAVE

Traditionally, all my life, I’ve been a loser in all the ways you could be a loser, but mostly socially, financially, and professionally. I’m deeply connected to its comforts; this constant state of loser-dom has allowed me to hide at the bottom or dive into it headfirst in dramatic fashion

I played sports throughout my childhood–baseball, basketball, and football, mostly–and showed some flashes of ability but would always collapse when there was real competition or stakes. When faced with the prospect of winning or losing, it’s much easier for me to commit to losing than to try to win because the idea of forestalling the inevitable is almost more painful than practicing one of the most essential Four Agreements: “Always try my best.”

As I mentioned in a previous essay, I took up Brazilian jiu-jitsu late last summer at the encouragement of a grappling trainer I met through this newsletter, Michael Weetman. I’d always been curious about trying the sport but was content to watch UFC fights from the comfort of my couch.

Eventually, I worked up the nerve to do it. But after a few classes, I didn’t love it. It wasn’t fun getting suffocated and hyper-extended and humiliated. I knew how weak-willed and anxious I was–I certainly didn’t need to pay for the added privilege of having strangers strangle me because of it.

BJJ also exposed another defect in me, something I like to call the “prodigy complex.” I only like to try new things that I could potentially be preternaturally gifted at. My fantasy is that I’ll discover a skillset that will completely alter my life’s path.

I hate to admit I’d indulged in this when I began BJJ. Think about that level of delusion: That my real-deal Brazilian professor with a coral belt who’s competed at the highest levels of the sport would pull me aside on the first day of class—49-year-old me clad in my cheap nylon running shorts and stretched-out white t-shirt with baby footprints on it my kids gave me as a Father’s Day present, no less—to tell me he “saw something in me” and that he’d be willing to train me for free for the rest of my life to help unlock my unlimited potential. I’ll relieve you of the suspense and reveal no such thing occurred.

But the beauty of the sport is that constant failure is one of its most important tools. Enduring the mental toil of consistently losing–and a high potential for injury–tends to rewire the brains of its practitioners into calmer, more resilient humans. And if you learn to be humble in both victory and defeat, the miracle will happen. Sound familiar? It’s the ideal sport for people in recovery.

I decided that even if I wasn’t good at it, I needed to stick with it because it would complement my recovery program. So I went two to three times a week, took several private lessons, and committed myself to show up to become something different than the person I was when I walked in there. But I knew I had my limits.

*****

In April, a classmate named Joe wanted to sign up for a BJJ tournament. He had been training only a little longer than I had, but he wanted to test himself and level up. He’s an extraordinarily kind and generous training partner, and I like rolling with him. I was genuinely inspired by his plan but also a little skeptical. But something moved me to commit. “Well, I’ll do it with you then,” I said. He smacked my leg and thanked me.

True to my word, I went home that night and registered for the Jiu-Jitsu World League Tournament in Anaheim on August 19. When I picked the weight class, I chose middle, which required its participants to be no more than 182 pounds and between 46 and 50 years old.

I was 189 when I signed up, which is heavy for me. But in sobriety, food–particularly food loaded with processed sugar—has become one of my new vices. Whenever I can’t sleep, I graze late at night for cookies, candy, or whatever I can get my hands on when I want to escape from my feelings of terror or worthlessness.

Even though I signed up for it, I doubted I would follow through. The thought of competing in a BJJ tournament at my age and with my non-prodigious skillset in a colossal gymnasium full of strangers was utterly terrifying. But I know that if I do flake out on this, I’d have to quit the gym altogether because I’d be too ashamed to go back in there ever again. So, instead of plotting out my training plan for the tournament, I thought about what excuse I could use to get out of it.

*****

By June, I’d begun to actively tell people that I’d signed up for a BJJ tournament, allowing myself to marinate in the ego boost that occurred when people responded with either shock or genuine admiration for what seemed like an incredibly ambitious goal. Before anyone got too emotionally invested in my plan, I’d quickly hedge and say that I had no chance of winning and my main goal was not to end up paralyzed. I said this to keep expectations low for people but primarily for myself because, as we’ve already established, I don’t know how to win.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Small Bow to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.