Notes From an Adult Child of Alcoholics

"They were always drinking, as far back as I can remember, in a way that I can now recognize as problematic, but at the time it was just the way things were."

Today's essay is from writer Anna Held, who shares a bruising account of life as both a child—and an adult child—with her alcoholic mother and father. Her dad got sober—but her mother was not. Left behind are the jagged remains and learning how to live after growing up with a life of disorganized pain caused by her family’s addiction.

"They were always drinking, as far back as I can remember, in a way that I can now recognize as problematic, but at the time it was just the way things were. As we got older, the drinking got worse. Slowly, then faster and faster, our family lost all of the things that people lose to addiction: jobs, licenses, money, relationships, health. By the time we left for college, the drinking had taken over everything. It burned all the oxygen in the room."

Anna has written about portions of her personal life for many well-known publications, but working on this was uniquely draining, given that she's never shared anything about her family before. I asked her if she was anxious about publishing it.

"As I say in the essay, this isn't something I talk about a lot. I worry that I am going to get pigeonholed as a writer who only writes about mental health and sad things when I think of myself as a pretty funny, optimistic person. I feel better with it in TSB vs. a publication with a more general audience because I'm less concerned about judgment. It's fine to judge me, but I don't want anyone to judge my family. I'm still a little bit nervous about showing up in an addict's inbox like, "Here's how you hurt your kid," but my hope is that this shows two examples of an honest way through."

It's a great one. Share away wherever you share great stories!

******

Btw: We’d love to publish more stories like this. We were able to pay Anna thanks to the money from paid subscriptions. We want to do more of these in 2025 and we love it if you could help us achieve that goal.

Also, we make a great gift.

Unclaimed Damages

Written by Anna Held

Edited by Tommy Craggs

Illustrated by Edith Zimmerman

My parents are alcoholics. I never really know how to tell people that as an adult. I live across the country from them, and they come up the way everyone’s parents do in a city full of transplants, as characters from a life they aren’t living anymore. There is this push to normalize addiction and mental health by talking about it, both to destigmatize it and get out from under the shame. I agree with the sentiment but miss on the execution every time, mostly because I have a hard time figuring out which part of the story is mine. Family members are on the fringes of addiction stories, children especially, who are often framed more as representatives of something to live for than full-blown people. And no one wants to hear about it, anyway, not really. I know because I told people, all the time, when I was growing up, and they said either I must have gotten something wrong or that there must have been a good, anomalous reason for their drinking, stress or holidays or whatever, or just because being a parent is hard, never mind of triplets. Or they told me that my mom and dad loved me, which I already knew.

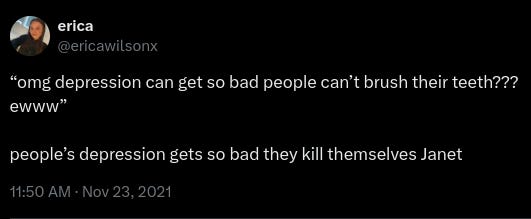

I often think about a Twitter post that says,

My dad nearly died from alcoholism and my mom drank herself into dementia. I don’t understand how anyone is surprised by anything else.

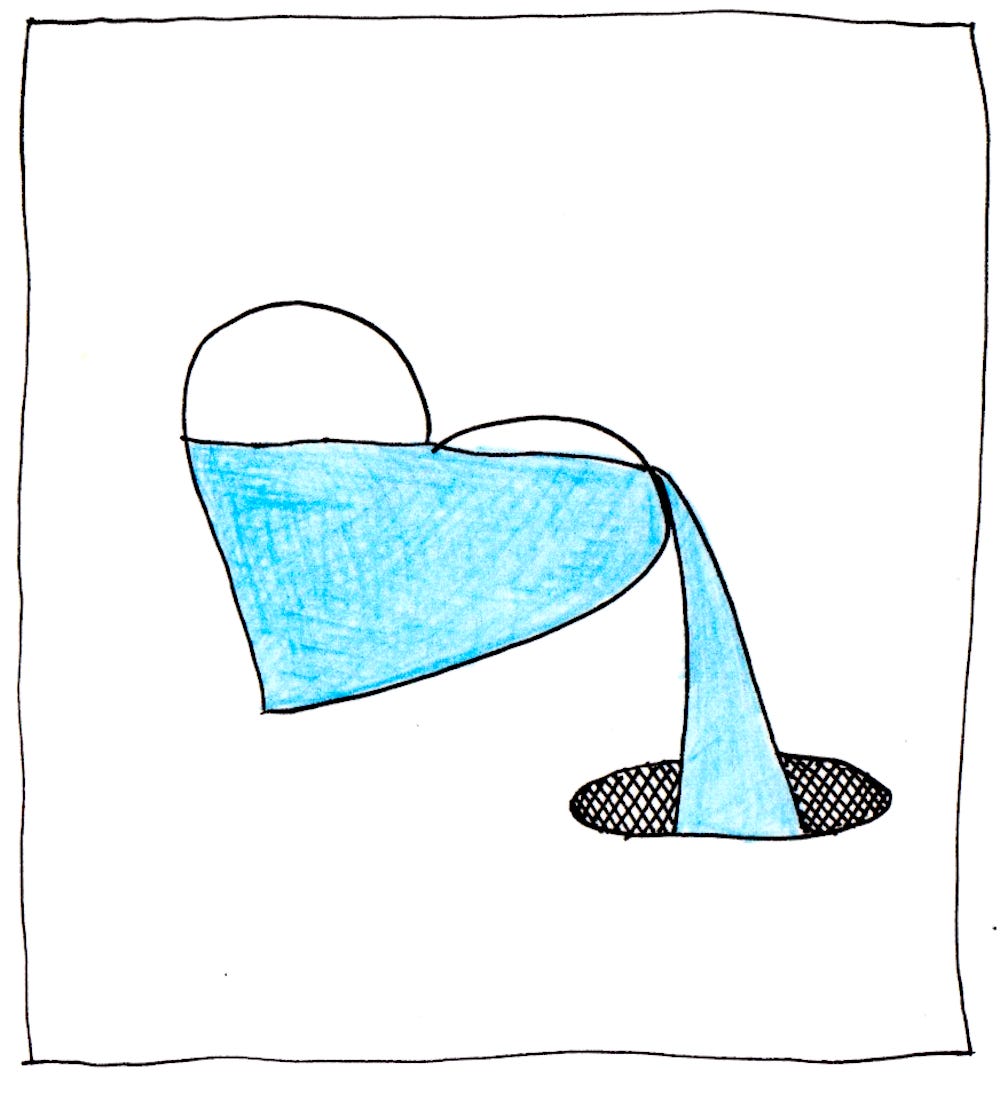

Once, when my brothers and I were ten or so, my parents drank too much at a neighborhood party and things got out of hand, a little worse than typical (cops) but not that different from any other Saturday. The house was quiet when we woke up, unusually clean. My mom gathered the three of us in the kitchen. She put an empty water glass on the counter and listed all of the things the three of us had done to stress her out the previous day. With each item, she poured water into the empty glass. We tried to defend ourselves and she talked over us, kept pouring water into the glass until it overflowed onto the counter, onto the floor.

This is the story that my brothers and I ask each other about the most. Do you remember it? Do you still think about it? Even now, I think of that morning with a deep, gouging shame. And I still don’t know how to explain that it was somehow harder to live in the morning after than it was to live in the night before.

*****

What I remember most about my early childhood is that we had a lot of fun. My parents took us places to do things at an intensity and frequency that I now know to be financially and logistically insane. We went to the kids' science museum, the Center for Puppetry Arts, the High Museum, the Chattahoochee Nature Center, and every playground and pool in the metro Atlanta area. In 1996 we went to both the World Series and the Olympics. My mom worked part-time so she could pick us up from daycare. My dad owned a dog treat business. You know the pig ears you give dogs? That was him. He came home every night smelling like smoke and pork fat.

They were always drinking, as far back as I can remember, in a way that I can now recognize as problematic, but at the time it was just the way things were. As we got older, the drinking got worse. Slowly, then faster and faster, our family lost all of the things that people lose to addiction: jobs, licenses, money, relationships, health. By the time we left for college, the drinking had taken over everything. It burned all the oxygen in the room.

This is where the stories diverge. I can point to it exactly, time and place. My dad was newly awake from the coma he was put in to survive his withdrawals, not to mention the emergency surgery to patch the myriad ulcers that had put him in the ER to begin with. My mom was in the ICU waiting room, hiding under the table where well-meaning friends and family drop off casseroles and coffee for the long haulers, drunk. The three of us were in the hallway talking to the nurses and the security guards, dividing up responsibilities, crash landing into adulthood.

When my brother tells this story, he always includes that, despite throwing up pints of blood, my dad drove himself to the hospital. My detail is that while he was under the knife, someone broke my grandmother’s window with what she assumed was a bomb, we assumed was a rock, and was actually a frozen plum. I missed my last week of classes and got knocked a letter grade on a final presentation. When I emailed my professor to ask him to raise it, his response amounted to, “But he didn’t actually die.” And that’s true. It was shocking how true it was. He was out of the hospital within 48 hours of waking up, at my college graduation two weeks later. He’ll be thirteen years sober next spring.

My dad’s story is tidy, resolved. Something terrible happened that forced incredible change. His recovery has turned me into an optimist at the most annoying level. I hold the unshakeable belief that every single person is capable of change beyond their wildest imagination, that we are all stronger than we can see or understand. I am punished by this belief all the time. It is easier to believe that people can’t change than it is to believe that they can but won’t, or worse, that they could have but it’s too late now. They’re too sick. They’ve missed their exit.

My mom is still drinking and has been very clear that she does not intend to stop. She went to rehab for the first time when we were 16, when her every-night drinking became all-the-time drinking. Once we got our learner’s permits, she would sit in the parking lot of the tennis courts or aquatic center and pour single-serving bottles of chardonnay into her Chick-fil-A cup and have my brother drive us home. For a few years she was in and out of treatment. She would get sober, string together a handful of good days or weeks at a time, and then relapse. I remember it being difficult at the time, and I’m sure I was angry. I didn’t realize that there were two ways for relapses to stop, and one was to stop trying. That feels like a very long time ago now.

*****

Ostensibly, I am writing about forgiveness. I am taking the fact that the transformations that have happened in my relationships with my parents feel nothing like forgiveness as a sign of growth. To err is human; to forgive is, famously, divine. Who are you, St. Peter? This is a joke my husband and I make whenever someone says anyone is a good person.

There is some irony here, in that I have been pushed to forgive my parents for my entire life, and I’m still not doing it. It has never felt like the right reaction to what was happening. There was a lot of capital-T trauma that happened as a direct result of the drinking. Together they amount to most of the worst days of my life. At the same time, there was a gift in their obviousness. There was no world in which whatever happened wasn't terrible, where I had no right to be upset or scared. We were all living in the same plain truth. Often, there was even paperwork.

It was much harder to figure out what to do with the smaller cuts, and the repetitive denial and diminishment of what was happening. Sometimes this was in the form of outright lies but mostly it wasn't. You can’t remember what you can’t remember. And their arguments—that they loved us and therefore wouldn’t ever hurt us—made more sense than the truth.

I still question if it was really as bad as I remember, if it’s as bad now as it feels right now. Sometimes I feel like I have no right to claim any damage at all because our grandmother moved in with us when we were in middle school and shielded us from the worst of it. She cooked for us and cosigned the leases to our first apartments and let us use her airline miles. And I had my brothers who were there and did know what happened, who sat with me at the top of the stairs. Wherever we were failed, we were also saved, or at least salvation is what it felt like to me. And what a gift that is, in any form for whatever reason, to be loved like that.

When I was introduced to the disease model of addiction in adolescence, it further tamped down any trust or allegiance I had to my own feelings. The logic went, if someone I love was suffering from a disease, anything I experienced as a result did not matter, or at least was greatly secondary, even as it commanded and tore through my life. When we left home, we were just ahead of the first big losses. It felt bad but materially, it wasn’t yet. Post-treatment, it was explicit that the drinking was not their fault, so us getting upset about it was misguided at best and triggering at worst. We had to take the hits and get up quickly, which was really no different from what we’d done our whole lives, we were just calling it something different. If that is forgiveness, I am still not interested.

In college, I wrote about my parents in my creative nonfiction classes where everyone was at the stage where they think writing well means exploiting the worst thing that ever happened to them. I made friends with a girl who had two different stepdads throw thousands of dollars' worth of formal china at their dining room wall as they were leaving her mother. We were walking out of class one day with another girl who had written something I don’t remember and she said, “I know that I haven’t had anything big happen to me but it’s not like things were easy. My dad really, really cares that I get good grades.”

And we said, “Of course, yes, that sounds hard. We don’t think we’re special because we had hard childhoods.”

Of course, that was a lie. Something big had happened to me. I did think I was more interesting. I also felt really angry, all of the time. I wouldn’t have identified it as that at the time. I still have a hard time locating it. But it was present then, my beating heart.

I called my grandmother every day and she would pass the phone off to my parents if they were around and sober. My dad described talking to me like pulling teeth. States away, I could live more easily in the day-to-day of their addictions—being able to hang up on them was game changing—but I was still petulant and seething. I made my pain disappear for you. And you didn’t care at all.

*****

My dad’s shift from life-threatening alcoholism to sobriety was extreme and destabilizing, like stepping back onto dry land. Still, it took a while for us to figure out the new version of our relationship, which to that point had evolved from fear- to rage-based. I resisted being parented because the way I saw it, both of my parents had given up the privileges of parenting—emotional access and telling me what to do—when they abdicated the responsibilities of it. I was grateful he was alive and deeply mistrustful of “getting sober.”

In this new world, my feelings still didn’t matter but that was a good thing. Practically, the extremity of his health situation made clear the true boundaries of addiction. If he drank even one drink, he would probably die. If he drank more, he definitely would. I could no longer question whether I had done something wrong or accept the facile blame for his mercurial temperament. We all knew the stakes. I was off the hook.

I’ve seen a lot of advice, including in this newsletter, telling parents to tell their kids—often in a letter—what they were going through in their addiction, how they were feeling and what they were thinking, to help make sense of what happened and why. To me, that feels like more of the same: another correction of the record, another instance of your story above theirs. An ungenerous part of me wants to respond, "Was everything up to this point not enough about you?" (Sorry, I'm working on it.)

To be more prescriptive, I don’t think we could have gotten to where we are now if he had not acknowledged the real and present damage we’d sustained due to his drinking as kids. That, along with seeing him do the actual work, was what gave us a path forward. He apologized at some point in the early years, and it was a nice moment but also kind of beside the point. On me and my brothers, there was a noticeable lack of pressure. He was going to do the work either way. He gave us the information, and we got to decide what we wanted to do with it.

Over time, we’ve let him be our dad again. He built the arch under which I got married. We ask him about home improvement and what things were like before we were born. He babysits my nieces and nephews and goes with them to the zoo. I still worry about him all the time. I don’t tell him when anything is going wrong in my life until it’s resolved because I’m afraid of something, though I’m not exactly sure what. Maybe the fear is the scar that lasts.

*****

About the damage. The crux of it is, I have a very thin sense of self. I do not have any instinct I can trust. And how I grew up might be why, but I’m not actually sure. Part of me has felt like this as long as I’ve been alive, which could be a point for either side.

I thought it was circumstantial. I’d assumed that the day-to-day drain of waiting for the other shoe to drop was the source of my capriciousness and that without it the brokenness I’d felt would precipitate out. Instead, I was mystified. I said and did things that were confusing, even in the moment. I was overwhelmingly agreeable, terrified to say no to any request no matter how unreasonable, then immediately resentful. How dare you let me do that to myself. I made choices only out of fear, unable to stomach the risk of losing anything, even things I wasn’t sure I wanted. Whenever I felt like someone was mad at me I would approach them with the energy of a dog licking another dog’s teeth in deference. The reasons I clung to were the obvious ones: that I was a bad person, hard to be around, difficult to love.

As I got older, I became more and more of a stranger to myself. As my mental health deteriorated, I became increasingly concerned that I was going to ruin my life. I was terrified of losing my job. I wasn’t worried my husband would leave me but that I would ruin his life, too, and we’d become two people who could have been happy but weren’t.

I knew where the road ended. I knew there was a way out, my dad showed me that, and I wanted to find it before I lost more than I could bear. In fits and starts, I got the help I needed. Medication helped turn down the volume on my feelings enough that I could hear my thoughts over them, and made them small enough to get my arms around. I ask myself questions like, “Is this true, and how do I know it?” and say things like, “The problem will be there tomorrow.” I question every instinct I have, every decision I make. I run everything I say or do over and over in my mind. It’s exhausting. I feel like I’m talking to myself all the time, like I am no longer a person but a conversation. I hope that as I continue to do the work, it becomes less difficult, or rather, I want to hope, but I shouldn’t. Hope is a feeling I have to question and talk myself out of.

*****

Last December, my mom introduced herself to me. She forgot my name but also forgot that she was supposed to know it, asking me if I was a Visiting Angel from my grandmother’s hospice care organization. I was so destabilized by her formality, the cheery politeness that is only extended to strangers, that I started laughing. That’s what I remember, laughing and her smiling at me as if she were trying to catch the joke. It was blunt evidence that the damage we’d known for years was coming had already quietly arrived. If my husband hadn’t been standing right next to us, I would have talked myself out of the fact of it happening at all.

Two weeks later, my grandmother died. She fell out of bed on Christmas Eve and died a few days later, just before the new year. Everyone said she was demented and didn’t know what she was doing but that’s not true. I know what she was doing. She was trying to check on my mother. I stood cold in the backyard on my phone, away from the din of my friends drinking and talking in the kitchen, and I tried to tell her how much I'd loved her, how she had made all the good things in my life possible. But she talked over me, saying over and over, “Take care of your mother, promise me, you have to take care of your mother.”

I didn’t know what to do with that anger, how even in the end, it was not about me or about us but about my mom, always about my mom, who two weeks before hadn’t known who I was. The anger doesn’t even make sense. It’s nobody’s fault. I can’t blame my grandmother for loving my mom or my mom for being as sick as she is. But what do I do with what I’m left with? How do I figure out how to live in a way that this sick feeling doesn’t poison me? How many times do I have to ask myself the same fucking questions?

That’s why these are terrible stories that no one wants to read or hear about, about the pain that doesn’t matter. When you are hurting for decades, there seems to be an expectation that you will have figured out how to handle it better. Mostly I have. Addiction is repetitive. The first slap teaches you that it can happen. The second slap teaches you it can happen again. And then you've learned all there is to know. What’s another late-night phone call, another broken bone? Walk away, deep breaths, give my phone to my husband. But sometimes something happens that takes my breath away, even still. And I forget all the things I’ve learned about how to be a person.

*****

It’s possible my parents set the conditions for my issues. It’s equally possible that I would have been this person no matter what. I was given the first tool to save myself when I learned that things will not get better without a feat of immense effort, and even then it’s not always enough; that things can and will get worse. When I felt myself slipping away, I knew beyond the shadow of a doubt what the stakes were. It did not matter how hard the work was or how much I resented having to do it. I knew what the choice was, what it would cost me. I suspect this knowledge will have saved my life. There is a world in which I am a dog treat heiress. There is a world in which I am dead.

With my dad, I don’t see forgiveness as something that is mine to grant but as a mutual recognition. I see that you’re trying. I’m trying, too. For my mom, forgiveness manifests as commitment to showing up, without contingencies. I cannot expect her to get better, and if I keep the hope, I keep the pain that comes with it. I can set my own boundaries to keep myself physically and emotionally safe, but I also have to accept that even the right decision comes with tradeoffs. If I want a relationship with her—and I do, I always will—it is up to me to figure out and enforce my limits.

The less I consider how things could be different, the more it feels possible to be happy here, now. But I still want my mom to get better. I try to wrestle pieces of her story into some version where this, right now, could be the beginning. I know this is delusional thinking given that she is clinically, with hard numbers, in the late stages of alcoholism, but my dad almost died from it and it was his beginning. I have worked very hard to accept that there is nothing I can do to push her toward sobriety. I cannot save her, and I know the script to tell myself when I start to slip. But the fact remains, whenever anything bad happens to my mom, really ugly things like smashing her face on the rim of the bathtub or losing her ability to walk unassisted, I wonder if this is the moment where things could turn around. Thank God, it’s going to be this, it has to be. And then it isn’t, and I’m the worst daughter in the world.

If I trace back my rage, that is where it comes from. I love my mom. To bear witness to her suffering feels impossible, and I know it feels worse to endure it. I rage at the truth that love is not enough, and at everyone who says it is. I rage at myself for being so hurt by what she says and does while drunk that I don’t appreciate or fully show up for the time in which she is sober. I know better, too. I’ve read all about how connection is what matters, and I hate myself for not being able to get outside of my own pain enough to offer it to her when she needs it so badly. She was in the ER a few years ago (drunk, fell, again), and she cried and the doctor had to tell me to hug her, and I think about it every day. I look in the mirror and see her face and my grandmother’s face and grieve for both of them, for all of us.

To paraphrase Leslie Jamison, it’s hard to know whether things will get better, but they have gotten different. We have all gotten married, the responsibility of our care and keeping offloaded. My brothers both have kids (I have two dogs and a baby names list in my notes app). Everyone’s parents are getting sick, not just ours. I’d like to think I can show up for my friends better by knowing what it’s like for the obligation of care to shift, or at least what’s most useful in a hospital waiting room. I am mostly okay, most of the time. But here I am, still, forever, waiting for another ordinary miracle.

*****

Anna Held is a writer and editor based in San Francisco. Her work has been featured in The Cut, Vox, Romper, Buzzfeed, and Runner's World, among other publications. She is a nonfiction editor at The Rumpus.

The world is hard. Pass along TSB as a gift this year and let’s do our part to change that.

ZOOM MEETING SCHEDULE

Monday: 5:30 p.m. PT/8:30 ET

Wednesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Thursday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET (Women and non-binary meeting.)

Friday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Saturday: Mental Health Focus (Peer support for bipolar/anxiety/depression) 9:30 a.m. PT/12:30 p.m. ET

Sunday: (Mental Health and Sobriety Support Group.) 1:00 p.m PT/4 p.m. ET

*****

If you don't feel comfortable calling yourself an "alcoholic," that's fine. If you have issues with sex, food, drugs, codependency, love, loneliness, and/or depression, come on in. Newcomers are especially welcome.

FORMAT: CROSSTALK, TOPIC MEETING

We're there for an hour, sometimes more. We'd love to have you.

Meeting ID: 874 2568 6609

PASSWORD TO ZOOM: nickfoles

Need more info?: ajd@thesmallbow.com

MORE MEETINGS COMING NEXT WEEK!

This is The Small Bow newsletter. It is mainly written and edited by A.J. Daulerio. And Edith Zimmerman always illustrates it. We send it out every Tuesday and Friday.

You can also get a Sunday issue for $8 a month or $60 annually. The Sunday issue is a recovery bonanza full of gratitude lists, a study guide to my daily recovery routines, a poem I like, the TSB Spotify playlist, and more exclusive essays. You also get commenting privileges!

Other ways you can help:

BUY A SANTA PILL MUG

TSB merch is a good thing. [STORE]

or you can

or you can give a

that goes toward the production of the podcast.

Everything helps.

A POEM ON THE WAY OUT:

The Conditional

by Ada Limón

*********

Say tomorrow doesn’t come.

Say the moon becomes an icy pit.

Say the sweet-gum tree is petrified.

Say the sun’s a foul black tire fire.

Say the owl’s eyes are pinpricks.

Say the raccoon’s a hot tar stain.

Say the shirt’s plastic ditch-litter.

Say the kitchen’s a cow’s corpse.

Say we never get to see it: bright

future, stuck like a bum star, never

coming close, never dazzling.

Say we never meet her. Never him.

Say we spend our last moments staring

at each other, hands knotted together,

clutching the dog, watching the sky burn.

Say, It doesn’t matter. Say, That would be

enough. Say you’d still want this: us alive,

right here, feeling lucky.

— “From Poets.org ”

"I rage at the truth that love is not enough, and at everyone who says it is." As the adult child of an alcoholic, wow, did that ever ring true.

It can take a lifetime and then some to untangle the effects of having alcoholic parents. We help each other recover by telling our stories and listening to the stories of others. I’m grateful for your openness and your honesty.