Recovery From Solitary Is An Illusion

“You can never go back to what you were, and what you could have been will always be out of reach.”

Today's newsletter is sponsored by Best Day Brewing, a non-alcoholic beer born in Northern California and crafted for doers everywhere. Because life is full of moments that deserve a great beer, but not the booze. Have a Best Day throughout Dry January — and beyond. Scroll to the end to learn more about Best Day's Dry January contest, the Best You Yet Adventure.

Good morning. Today is our first collaboration with Empowerment Avenue’s “Writing for Liberation Program,” a “one-on-one volunteer model in which outside editors and writers are paired with incarcerated writers to work together to workshop and publish the incarcerated writer’s work.”

The featured essay is from Kevin Light-Roth, currently serving 28 years in a Washington state prison. He wrote a short, lyrical essay about what it’s like to spend months in solitary confinement that is full of poignant, poetic, unforgettable terror.

“You will begin to understand that recovery from solitary is an illusion. A lie necessitated by the perceived loss of the person you imagine you could have been. You can never go back to what you were, and what you could have been will always be out of reach. The version of you that might have come to be without solitary confinement — without disadvantage, without all the destructive decisions and cruel luck and tragedies you wish you could undo — is not something that can be reclaimed.”

I have wondered about solitary and if there is ever a point when it becomes a luxury — that to be away from other prisoners and in the safety of your own cell would actually be the better deal. I have considered the full extent of the physical and mental anguish, the brokenness that occurs as part of the trade-off. However, I never realized, until I read Kevin’s essay, how important it is to endure the time there, and to never adapt to those conditions. Adapting is its own form of death because you may never be able to feel human again.

*****

We can fund these unique stories as long as we continue growing our paid subscription business. We’d love to have you and everyone you know subscribe.

If the cost of a subscription is prohibitive, or if you wish to send TSB to someone you love, contact us. We’ll happily pass along a free annual subscription to those who need it most. — AJD

When you’ve been in the hole long enough, even your dreams take place in a cell…

by Kevin Light-Roth

This will set in after about six months. You put a letter out through the slot in your cell door to mail it, then find the same letter sitting on your desk and realize you only mailed it in a dream. You dream of petty catastrophes — knocking your radio off the desk and breaking it, losing your only pen…

You dream, constantly, of fighting with the guards. Your cell door slides open and a squad of them rushes in to attack you, or you impulsively slip your handcuffs during an escort and punch one, incurring new rule infractions and extending your time in solitary. You wake with your chest cinching down on your lungs, panicking.

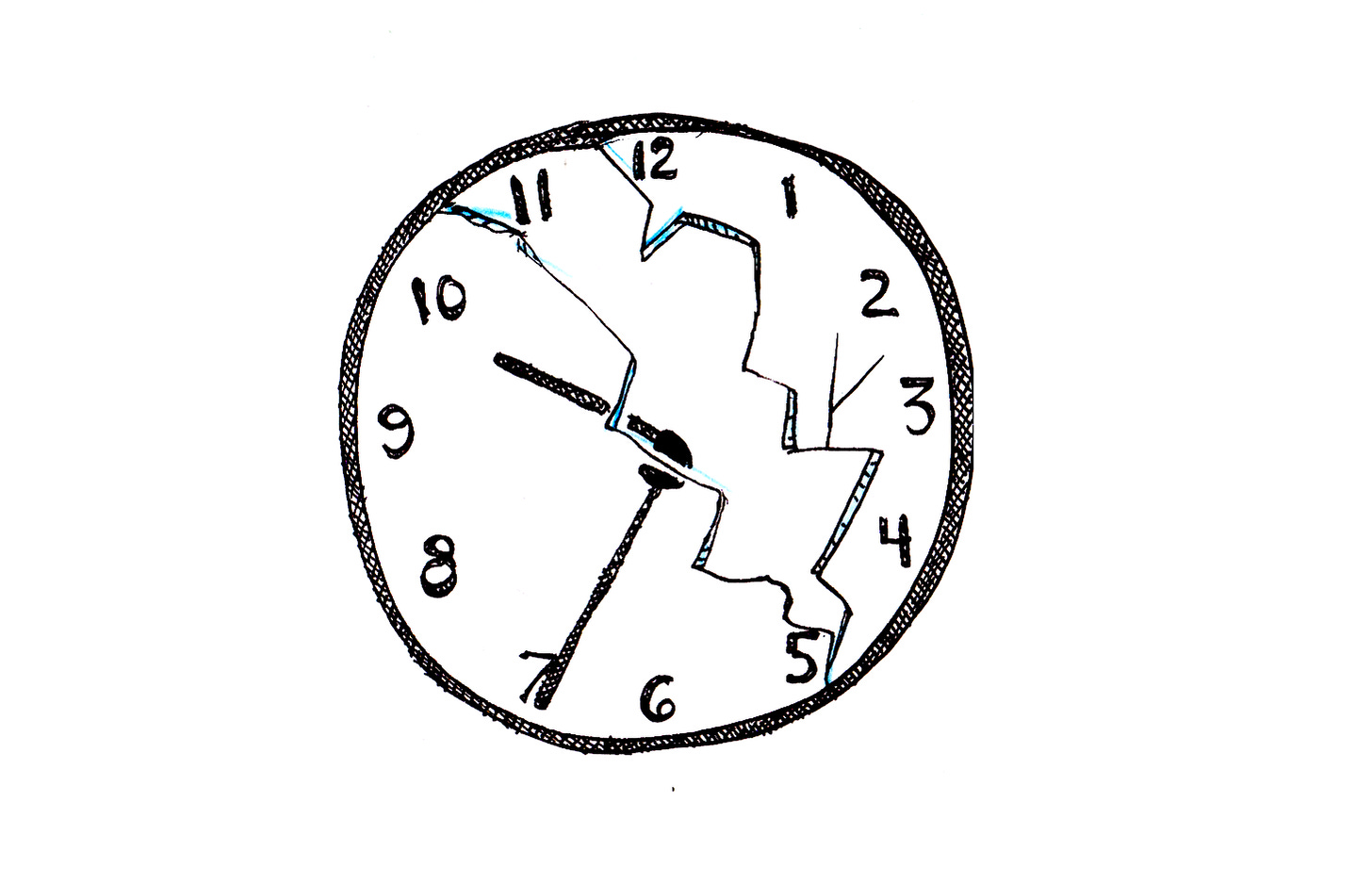

As the months of isolation proceed, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish dreams from reality. Then reality itself takes on a dreamlike texture. You drift between the sad little tasks you’ve invented to give your day a semblance of purpose. Making your bed and stretching the threadbare wool blanket to a pristine smoothness, tucking and re-tucking the corners. Cleaning the cement floor with a washcloth and soap. Getting the edges of the papers on your desk lined up just so.

You forget what you’re doing as you’re doing it. Your brain’s neurons seem to sputter when they should be firing. To focus on anything for longer than a few minutes is impossible. Try to get a letter going, or read, or think along a linear course, and your thoughts turn to ether.

Your mind retreats into daydreams and your daydreams grow complex and immersive. They tug you along on a course of their own devising, heeding none of your direction. Invariably, they involve conflict with someone, a real person from the life you once had or some imagined antagonist. You pace your cell reciting aloud the clever points you would make to these chimeras, issuing ultimatums to them. The daydreams are in no way pleasant and altogether unwanted. They enrage you.

Then a transformation takes place. After nine months in the hole, maybe a year, your psychological rhythm shifts to match the tempo of solitary. You lose all desire to get out of your cell. Five days out of the week you are allowed one hour in the concrete dog run that serves as a recreation area, but you decline that time out more often than not, only leaving your cell if you need to make a phone call. At length, you start skipping those, too. People won’t hear from you for weeks on end. They will assume you’re being mistreated.

When you shower — three times per week in a four-foot by four-foot cage at the end of the tier — you finish quickly and flag down the guards to take you back. Returning to your prison cell feels like returning to sanctuary.

You can feel yourself slipping toward total dissociation, becoming unmoored from the physical world. And you want it to happen. You will not be able to admit it, least of all to yourself, but you want to let go of reality. You don’t want to deal with the world anymore and you don’t want to get out of solitary.

One day, they release you. You never know ahead of time when it will happen. Early on a random morning, guards appear in your cell window and tell you to pack your things. Everything you own fits easily inside a paper sack. They handcuff you and take you down the hall to a holding cell, and they strip-search you as if there is anything in solitary worth smuggling out.

The guards throw your jumpsuit and rubber sandals into a bin and give you a standard prison uniform. Pants feel oddly restrictive. Shoes are heavy and cumbersome to wear, and your feet are sweating from the instant you put them on. Your toes will hurt for days.

You step out alone onto a main prison walkway. The open expanse of the sky disorients you. The sunlight stings your eyes, and they will water continuously any time you go outside this first week. Walking without handcuffs feels bizarre — you aren’t sure what to do with your unrestrained arms. They dangle awkwardly at your sides like a chimp. Making your way to a living unit, part of you is exhilarated. The rest is a churning knot of anxiety and apprehension and jumbled, careening thoughts.

In general population, every social interaction makes you uncomfortable. Friends want to shake hands and embrace you. The physical contact puts you on edge. Eye contact produces tension in you. People stand too close and their movements seem spastic and combative. Their voices are too loud. You feel like a forest animal dropped in the middle of a carnival. Something dangerous is spring-loaded inside you and you don’t know what might trigger it, or what might result. You are perpetually afraid that you will come unhinged in some unpredictable way.

Looking in a real mirror for the first time in however long, months or years, you discover yourself physically diminished in ways that border on frightening. It’s more than the weight loss, though that is dramatic. You’re skinny. You have aged, with furrows carved into your face and gray seeping through your hair. Your skin is dull and taut over your skull, the bone structure of your face made stark. You don’t look like a prisoner, you look like a warzone refugee. Meeting your reflected stare, you see something wild and unfamiliar in your own eyes.

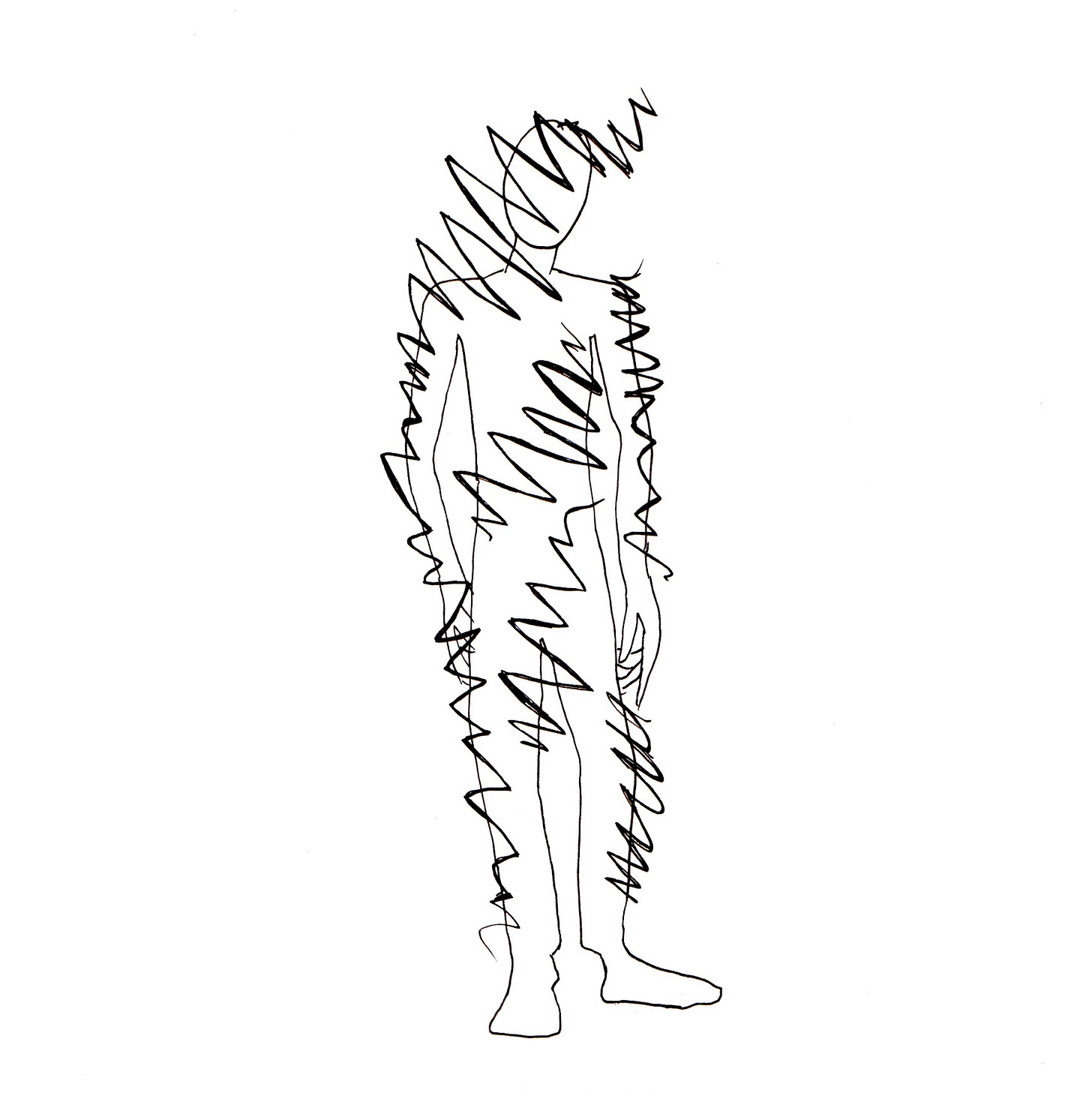

It will take weeks for you to mentally reset and become a recognizable version of yourself. In that time, you will think of all the people you have seen permanently and horrifically altered by solitary. Men psychologically shattered, their core personalities disfigured. You have an overriding fear that you will never recover. That an essential part of you is irretrievably lost.

And you will wonder, well after you achieve the feeling of recovery, whether recovery is even possible. Because if who you are is the sum of your personal experience, the grand total of what you’ve seen and felt and learned over your lifetime, then a large component of yourself is, and always will be, the years you spent in solitary confinement.

You will begin to understand that recovery from solitary is an illusion. A lie necessitated by the perceived loss of the person you imagine you could have been. You can never go back to what you were, and what you could have been will always be out of reach. The version of you that might have come to be without solitary confinement — without disadvantage, without all the destructive decisions and cruel luck and tragedies you wish you could undo —is not something that can be reclaimed. It’s something that never existed, and never will. You will come to accept, after extensive struggle, that to mourn its loss is to mourn nothing at all.

But from time to time, you will mourn it anyway.

*****

Kevin Light-Roth is a freelance writer currently incarcerated in a Washington state prison. He is a member of Empowerment Avenue, a collective of incarcerated writers and artists, and his work has appeared in The Guardian, The Hill, The Seattle Times, and elsewhere. Connect with him on X at @KevinLightRoth.

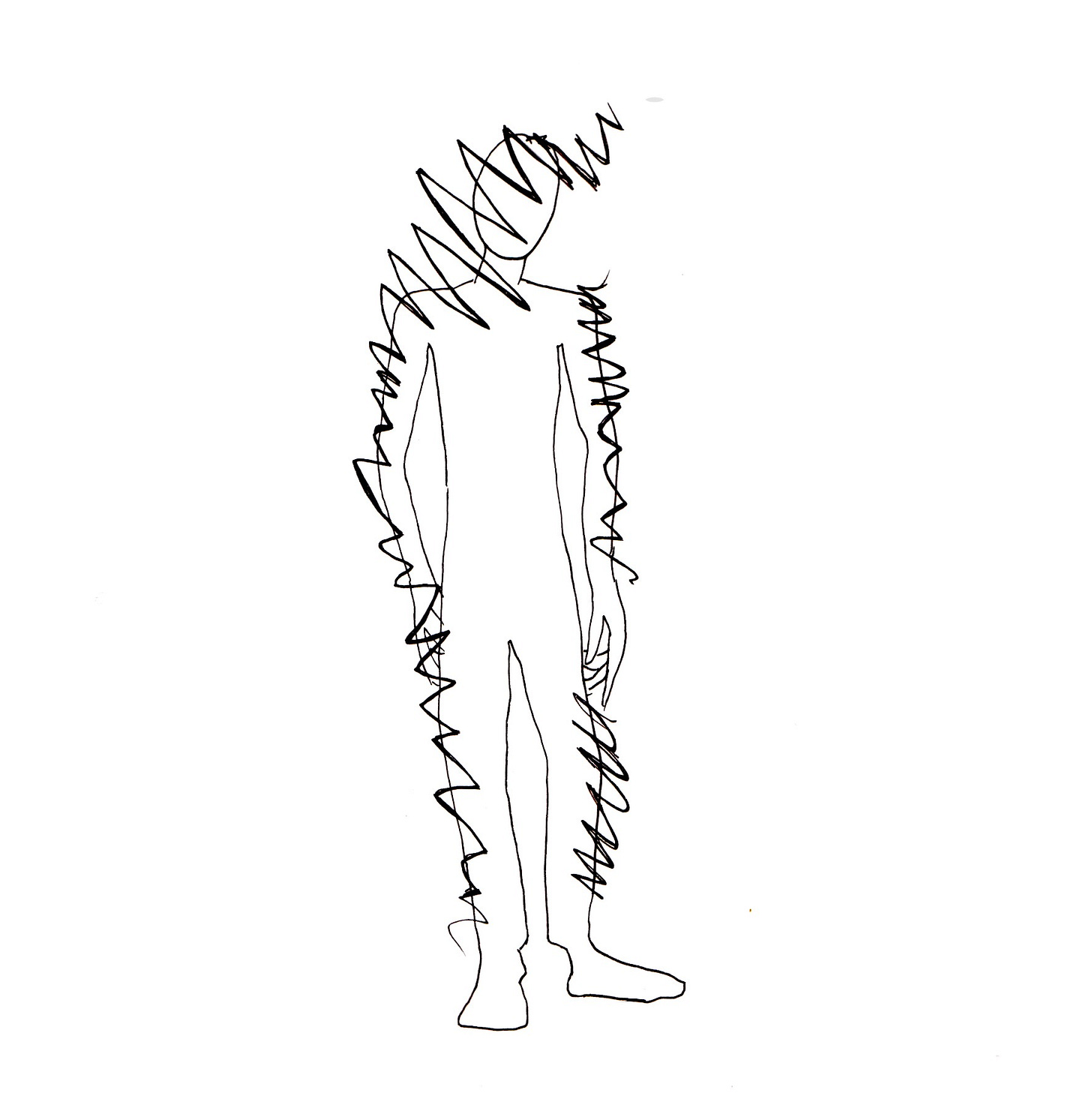

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY EDITH ZIMMERMAN

MORE FEATURES:

Notes From an Adult Child of Alcoholics

ZOOM MEETING SCHEDULE

Monday: 5:30 p.m. PT/8:30 ET

Wednesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Thursday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET (Women and non-binary meeting.)

Friday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Saturday: Mental Health Focus (Peer support for bipolar/anxiety/depression) 9:30 a.m. PT/12:30 p.m. ET

Sunday: (Mental Health and Sobriety Support Group.) 1:00 p.m PT/4 p.m. ET

*****

If you don't feel comfortable calling yourself an “alcoholic,” that’s fine. If you have issues with sex, food, drugs, codependency, love, loneliness, and/or depression, come on in. Newcomers are especially welcome.

FORMAT: CROSSTALK, TOPIC MEETING

We’re there for an hour, sometimes more. We’d love to have you.

Meeting ID: 874 2568 6609

PASSWORD TO ZOOM: nickfoles

Need more info?: ajd@thesmallbow.com

This is The Small Bow newsletter. It is mainly written and edited by A.J. Daulerio. And Edith Zimmerman always illustrates it. We send it out every Tuesday and Friday.

You can also get a Sunday issue for $9 monthly or $60 annually. The Sunday issue is a recovery bonanza full of gratitude lists, a study guide to my daily recovery routines, a poem I like, the TSB Spotify playlist, and more exclusive essays. You also get commenting privileges!

Other ways you can help:

BUY A COFFEE MUG FOR YOUR BOOKS

[STORE]

Or you can support Edith directly!

Demon With Watering Can Greeting Cards [Edith’s Store]

Other ways:

or you can give a

that goes toward the production of the podcast.

Everything helps.

A POEM ON THE WAY OUT:

Prisoners

by Luljeta Lleshanaku

*********

Why this fear?

What can be worse than life in prison?

Having choices

but being unable to choose.

— “Poetry Foundation via Child of Nature.”

In honor of Dry January, Best Day is giving away a Best You Yet Adventure in Jackson Hole with Alpenhof Lodge, Rivian, The North Face, and Yeti (up to a $7,288 value) to one lucky winner and their guest for a 4-day trip between June 1, 2025 - June 30, 2025.

This is barbaric.

I can imagine how difficult that solitary confinement for so long could be.

During my crazy days when I was in a reformatory, I was involved in a fight with a coworker. Unfortunately, it was midday on a Friday and the disciplinary hearings were only held on weekday mornings. I spent 3 nights in solitary confinement waiting for the next hearing. It was a horrible experience that I never want to repeat!

We humans are social creatures and most of us need our daily dose of community to remain healthy and sane.

Thanks for sharing this story!