The Alcoholic's Playlist Is Full of David Berman

"I ran through a stop sign on August 7, 2019, the same day Berman hung himself. It was, in fact, the last day I drank."

When David Berman died in 2019, there was much public mourning from the social media accounts of some of the moodiest, dreamiest writers and musicians I admire, but I had no idea who David Berman was. Yes, I had heard of The Silver Jews, but never once had I listened to them. I felt left out—kind of like I felt left out after John Prine died, but I was slightly familiar with some of his more popular songs. But David Berman never came into my orbit, not once, even when there was ample opportunity for him to do so, especially during my frequent sojourns into a strict alt-country music diet.

I didn’t dive right into his music until later, but in the immediate #RIP pile-on, his poem “Snow” kept getting passed around, and that was all it took because right then and there, I understood why so many people were crushed.

Then I did a very impulsive thing and purchased a first edition of his poetry book “Actual Air” on eBay for more money than I should have but it felt like a spiritual offering. It’s one of those books you can crack into 100 times a year and always discover a new phrase tucked away, one that appears just when you need it most.

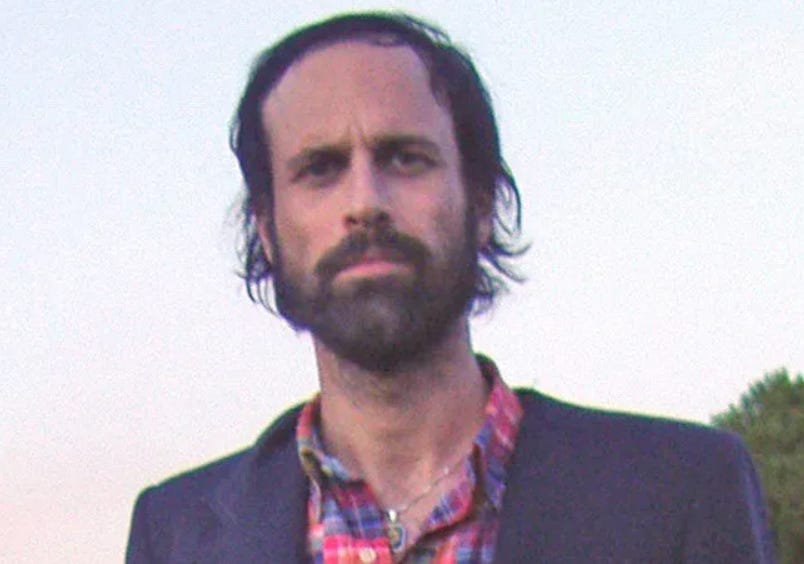

Today, I’m happy to share an essay written by one of my favorite writers (and a credible, before-death David Berman fan), Ben Gaffaney, about how Berman’s suicide intersected with his own alcoholism and eventual sobriety. It’s fantastic and I hope you love it as much as I do. — AJD

The End

of

All

Wanting

by Ben Gaffaney

************

Here’s a story: I was listening to “That’s Just the Way that I Feel” by Purple Mountains on the day I wrecked my wife’s truck. Here’s the truth: I was drunk on a Wednesday, the way I always was. I was in tennis clothes because I’d told my wife I had a lesson on Wednesday nights, allowing me to drink in the office till 8, then use the drive home to verbally practice stories about the lesson. I planned to give her an update on a fellow player, “Phillip Feetshoes,” who played in Vibram FiveFingers instead of tennis shoes. I’d mentioned him before; he was modeled after a regulatory lawyer I knew. It was summer in Austin, but I had the heat on high so I’d have a post-workout sheen of sweat when I got home. I thought about pretending the next lessons were a half-hour later, for 30 more minutes of vodka. Then I ran a stop sign, a subcompact smashed into the passenger side, I blew three times the legal limit and went to jail for the night. I vaguely remember trying to laugh off my field test performance and telling the police that the plastic zip lines they used instead of cuffs were environmentally unfriendly.

I don’t actually know what song I was listening to, but it would have been a perfect story: the lead single from David Berman’s final album, chiming “The end of all wanting is all I’ve been wanting” as I ran through a stop sign on August 7, 2019, the same day Berman hung himself. It was, in fact, the last day I drank.

******

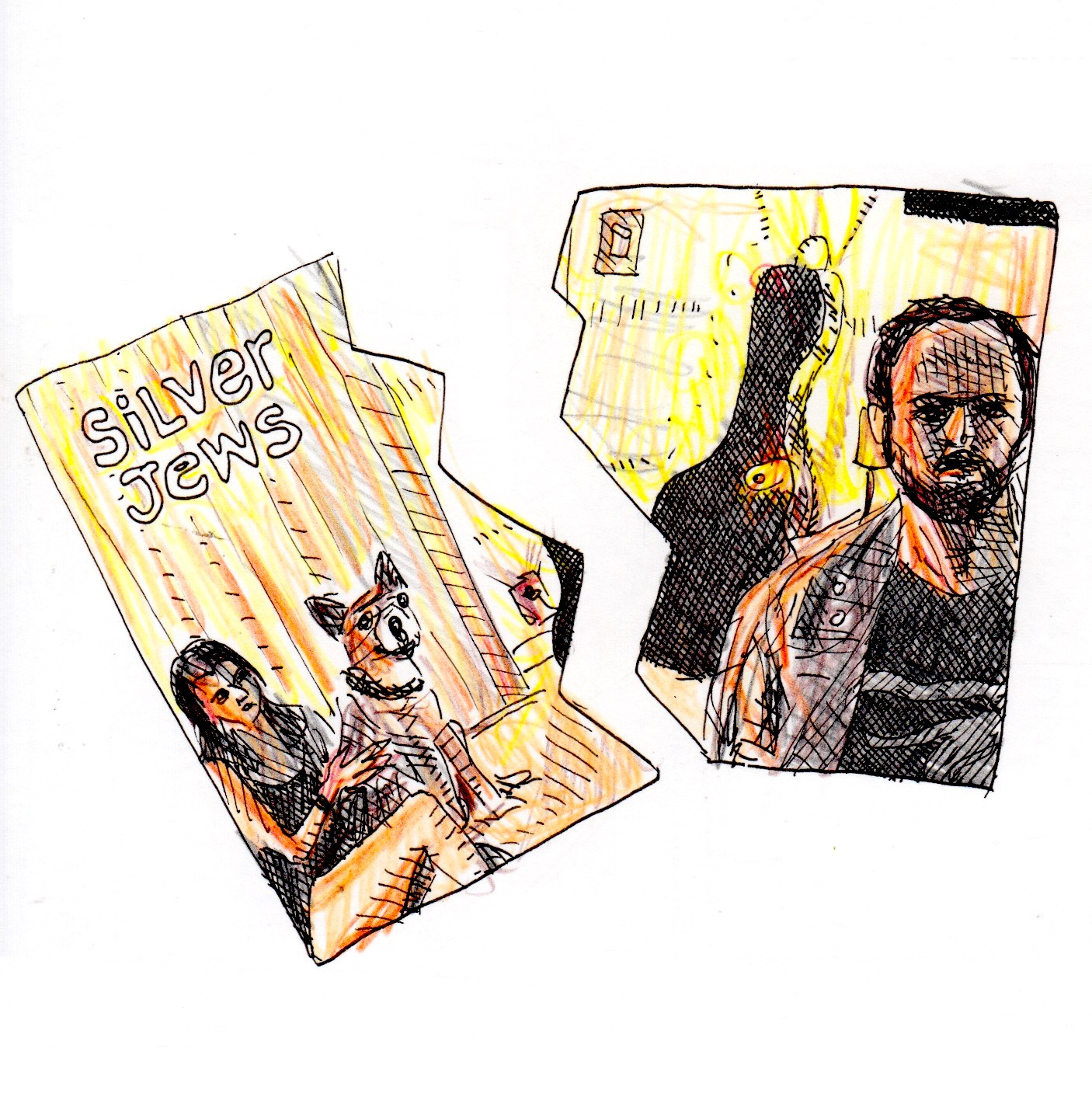

David Berman founded the Silver Jews, a band that’s been characterized as indie, indie-rock, alt-country, and Americana, among other designations. Berman released six albums from 1994 to 2008 and disbanded the Silver Jews in 2009. “American Water,” released in 1998, was probably the most successful album, when the Silver Jews also included Stephen Malkmus of Pavement, a college roommate of Berman’s. He also attended the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst in the mid-90s and released a poetry collection in 1999. When he released his final album under the name Purple Mountains in 2019, it seemed to me like a next act was beginning for his music, but then he died.

By all accounts, Berman was years sober from 2003 until his death. When he was using, he was shockingly productive, creating a pretty good book of poems and four beloved albums with the Silver Jews before he quit. Then, while clean, he recorded an addiction record (“Tanglewood Numbers”) and a recovery record (“Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea”). Like a lot of addicts, even ones with tangible artistic success, he died in debt. August 7, 2019, wasn’t his first suicide attempt. As chronicled by Nick Weidenfeld in The Fader – the most revealing and detailed David Berman interview – in 2003, Berman took 10 Xanax at a time while doing chores, with the intent to down 300. Somewhere along the line, he blacked out. But he survived that time.

*****

My first encounter with Berman was at BookHaven, an indie bookstore in Philadelphia near Eastern State Penitentiary. I flipped through “Actual Air,” liked the shape of the poems and saw it was blurbed by James Tate, my favorite poet. Berman’s work was straightforward-strange in a way I liked, where both language and concept were pitched at a surrealist level mild enough to keep you from getting too unmoored. It was like the work I tried to write and felt like I could write if I wasn’t too arrogant and lazy, pretending to have an MFA I didn’t come close to finishing.

Throughout the book, Berman’s narrators are often in states of separation, actively not participating in the action, refusing to acknowledge which things are happening and which are not. “Imagining Defeat” has lines that rhyme:

I reached under the bed for my menthols

and she asked if I ever thought of cancer.

Yes, I said, but always as a tree way up ahead

in the distance where it doesn’t matter.

I was moved by the straightforward treatment of the sort of odd conversation you have with a long-time partner. In 1999, I hadn’t heard his music yet, but I like to imagine he conjured some wobbly college-country into my ear from the start. What I felt most – and even wanted to feel – from Berman’s book was the wisdom of a man who’s been left a lot.

“Imagining Defeat” keeps momentum with unexpected turns of nouns: a plum, an inhaler, menthols. The “She” has a bus ticket, then she’s gone. He’s going to die some day and there’s only one path there, the only variable is the length, perhaps adjustable by giving up the menthols. Did she leave him because of his fatalism? She left him just the same.

*****

Around the same time, I became an alcoholic. I largely avoided alcohol before my mid-20s due to a long family history. Three of my grandparents were alcoholics, At least five close relatives have been to rehab.

So I never had a sip of peppermint schnapps at a young age that presaged an alcoholic future. I didn’t hide vodka in the garage, then sneak a shot on a minus-20 degree day in Chicagoland, sending myself to the ER.

Instead, I became an alcoholic at a New Year’s party in Chicago. I was helping set up and someone poured me a plastic cup of vodka, since I didn’t care for beer or wine. It was the dregs of the bottle and the cup was so full it had an outward meniscus. I sipped it immediately to keep it from spilling, didn’t care for it, then finished those 10 ounces of vodka, then another cup an hour later.

My cortex was liberated. I indulged in my mid-20s horniness, leading to accidental public sex, where I thought my girlfriend and I were on the other side of the bathroom door. I held court with stories and jokes. The host had hung a paper banner for everyone to fill in various prompts, and one was “Most Embarrassing Memory.” When my girlfriend wrote, “Tonight,” I was proud, not ashamed. The consequences were physically severe, including hours of vomiting, heels bloodied by cheap shoes, and days before I could ride in a car again without nausea. But that night, every reservation I’d ever had was obliterated, and I wanted to feel free of myself again and again. Berman’s addictions were cocaine and heroin, a pairing that’s often fatal. Of the handful I knew from rehab with that pair of drugs of choice, four relapsed and died shortly after discharge. “Tanglewood Numbers” makes its mission clear from the start with “Punks in the Beerlight”: “Where’s the paper bag that holds the liquor / Just in case I feel the need to puke.” It feels like songs of the newly sober, still working through how to laugh at what you’ve done. “There is a Place” from that album also includes the line, “I could not love the world entire,” which represents the sadness I felt most in early sobriety. It’s depression plus failure.

One AA truism says if you remember your last drink, it’s not your last drink. I hope that’s not the case, because I very much remember pouring the dregs of a handle of Tito’s into a plastic cup while at my standing desk playing round after round of “Into The Breach.” I remember it clearly, how the pour was several ounces more than expected, thinking “I better not drink all of this.” I drank all of this.

*****

Let’s talk about David’s father, Richard Berman.

I have a LinkedIn overlap with Richard Berman. I’ve worked in corporate communications and legislative and regulatory policy for 25 years, and I have a complete understanding of what Richard did for a living, the hours and devotion needed to achieve his level of success, and how much large companies are willing to pay to contract with guys like him.

Richard Berman is retired now, but at his peak he was a wildly successful lobbyist and communications strategist for some of the worst industries. He claimed to fight over-regulation, which meant, for example, opposing MADD for its efforts to lower drunk driving blood alcohol levels. Working for various hard-to-track coalitions, he fought successfully against any increase in the federal minimum wage. He was less successful in reducing tax levies on tobacco.

His son lamented that his entire artistic output could never undue even “a millionth” of the damage his father wrought on the earth, as if that was up to David. This is a classic superhero narrative, that the son must battle the sins of the father, like they’re both Jedi knights.

I’m in between them. I helped draft a coal company’s first Corporate Social Responsibility report, extolling its safety record as a way to deflect from its environmental record, just before one of its mines collapsed, killing dozens. I wrote the fucking safety section.

My alcoholism was absolutely fueled by the fact that I’ve never chosen a path in my life. I didn’t know how to study, so I dropped out of the University of Illinois’s chemistry program. I switched to rhetoric because that’s where the creative writing classes were. I had never written a short story but one of my older brothers had and it seemed fun. Then I went to graduate school in Boston because the woman I was dating went to law school there and I couldn’t think of anything else to do. I dropped out because my grad school funding was dependent on me staffing the computer lab and I never showed up, and besides I could always just claim I had an MFA, who was going to check?

If Berman felt utterly inadequate to battle the ills of capitalism and Richard’s role in it, that’s a great reason to use. I felt the same for my role in “burnishing reputation haloes to allow for greater operational latitude,” as my old company’s promo materials put it. I definitely drank over that.

Berman’s writing is hard to categorize. He wasn’t confessional, exactly, but he was earnest. Even his metaphors had a lived-in quality since they’re so idiosyncratic. My favorite: in “Black and Brown Shoes” Berman explains that he always wears a corduroy suit because it’s “made of a hundred gutters / That the rain can run right through.”

He was not at all afraid to make the listener uncomfortable, such as on “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son,” from “Purple Mountains.” The song has no narrative momentum, just longing and pain. It includes extended repetition of the phrase “she was” as an outro as the song’s narrator is wrestling with himself to accept that past tense is something he can reckon with. When I first listened to the full album, I found this song kind of flat and it became an immediate skip. Now it’s an immediate skip because I can’t handle that kind of sadness.

*****

I mentioned earlier that Actual Air has a blurb from the poet James Tate. It reads in part: “David Berman’s poems are beautiful, strange, intelligent and funny. They are narratives that freeze life in impossible contortions.” During my two semesters at Emerson College, which I’d entered as a fiction writer, the poet John Skoyles lent me his copy of Tate’s “The Lost Pilot,” a wildly successful first book written when Tate was 23. I’ve never loved a book of poems more, the same way you feel the first time you heard your favorite band.

Berman was a student of Tate’s at UMass-Amherst, and, unlike many book blurbs, I think Tate nails what works in Berman’s art. That stasis. That weird, weird stasis.

I am in bed late at night

in my house near the airport

listening to the jets fly overhead,

a strange wife sleeping beside me.

David Berman, From “Self-Portrait at 28,” Actual Air

I don’t believe Berman kept a blog or published a memoir. Perhaps he was an artist who saw his work as his memoir. He hated his father, or at least his father’s work. He looked for a balance between heroin and cocaine to allow him to produce meaningful art and release it without becoming overcome by self-hatred. He hid (and didn’t hide) his larger concerns behind irony; he just made you look for them, but only a little.

He also very much depended on love. “If no one’s fond of fucking me /Then no one’s fucking fond of me,” from Purple Mountains, is clever, resigned, and exactly the sort of thing to be explored in a Fourth Step Inventory. Berman and his wife, Cassie, had separated by the time Purple Mountains was released.

But he could be romantic as hell.

Way, way out past where the sidewalks disappear

And up through bright blue blocks of sky

Where the days turn to weeks into months of the year

And we’re together, you and I

“We Could Be Looking For the Same Thing,” from “Lookout

Mountain, Lookout Sea”

*****

And that’s where I feel the most kinship. In 1999, I leapt headlong into a giddy first marriage with a woman I barely knew. We met at the wedding of my high school best friend and her high school best friend and because we both loved words, we fell in pen-pal love, sending handwritten letters even though email was an option.

We had a whirlwind courtship. Sometimes I’d drive all night from Philadelphia to Athens, Georgia, for a weekend. Once, we met in Raleigh, where I bought a plastic ring from a Winn-Dixie vending machine and asked her to marry me.

We moved from Philadelphia and Georgia to Portland, Oregon, after spinning a coin on a map at the airport, and we were married before we ever lived in the same city.

It would have been a nice story if it had worked out. Or at least a pretty good country song.

We got on great as friends, but we were incredibly ill-suited to each other and likely would have split after a few months if we hadn’t committed to each other in a Unitarian church in Atlanta. Yet in 2003, when it ended, I lost my mind. I believed I was supposed to be a married man with kids and a corporate job, and had a full-on identity crisis when she moved out.

I recognize that now, but, at the time, I ramped up to one bottle of vodka and a couple of bottles of wine per day, more on the weekends, and started and ended two more marriages. I got a little more functional, but I drank daily for the next 16 years, up until August 7, 2019.

*****

On my last drinking day, I wrecked a 6,000-pound truck in a heavily populated area, and somehow I didn’t injure anyone. I went to jail, but not prison. A few days later, just before I went to rehab, I found written in my pocket notebook, “Why doesn’t anyone know how sick I am? Why doesn’t anyone care?” in giant letters across two pages, hand-shredded them and buried them under the wet food trash. If I’d died the same day as David, it would have been my suicide note.

Over nearly five years of sobriety, I’ve found so much strength in listening. At AA, I make a point to turn and watch the person sharing unless it appears to bother them, because I want to do my part as part of a collective, which isn’t easy for a loner like me. I feel a lot of relief when I share, but I gain strength from others, hearing every share as a tiny segment of a longer story to come.

But when someone dies, particularly an artist, they become a complete story, with a beginning, a middle and an end. I normally can’t help but put the artist’s work into context after the fact, knowing the work is done.

In years one and two of sobriety, I was so focused on simply keepin’ on, it didn’t occur to me that I deserved ambition. In year three, I adopted a mantra, “There’s more to life than could-be-worse.” As much as I love the proto-Buddhist principles of early recovery, I realized that I didn’t want to just be, I wanted to share and, most of all, to connect.

David Berman’s songs and poems feel like shares for everyone, from a real person in the room unsure what to do with their pain, their joy or even the jokes they can’t share with anyone else.

So I gain strength from him, too.

******

Ben Gaffaney lives and writes in Texas. More of his work can be found at “Hopping Off the Bus to Abilene.”

For Further Reading:

“Approaching Perfection” [Welcome to Hell World]

For Listening:

This is The Small Bow newsletter. It is mainly written and edited by A.J. Daulerio. And Edith Zimmerman always illustrates it. We send it out every Tuesday and Friday.

You can also get a Sunday issue for $8 a month or $60 per year. The Sunday issue is a recovery bonanza full of gratitude lists, a study guide to my daily recovery routines, a poem I like, and more exclusive essays. You also get commenting privileges.

Here’s our most recent Sunday issue:

Baby Reindeer

If you already have too many newsletters in your inbox but would still like to help our publication succeed, you can make a one-time or monthly donation by pressing this button.

Or if you like someone an awful lot, you can give them a subscription.

Thank you so much for your support! Follow us on Instagram if you want more of Edith’s illustrations. We also have merch.

NEED A MEETING THAT’S NOT LIKE THE OTHER MEETINGS?

ZOOM MEETING SCHEDULE

Monday: 5:30 p.m. PT/ 8:30 p.m ET

Wednesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Thursday: (Women and non-binary meeting) 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Friday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Saturday: Mental Health Focus (Peer support for bipolar/anxiety/depression) 9:30 a.m. PT/12:30 p.m. ET

Sunday: (Mental Health and Sobriety Support Group) 1:00 p.m PT/4 p.m. ET

*****

If you don't feel comfortable calling yourself an "alcoholic," that's fine. If you have issues with sex, food, drugs, DEBT, codependency, love, loneliness, depression, come on in. Newcomers are especially welcome.

FORMAT: CROSSTALK, TOPIC MEETING

We're there for an hour, sometimes more. We'd love to have you.

Meeting ID: 874 2568 6609

PASSWORD TO ZOOM: nickfoles

The Homeowner’s Prayer

by David Berman

*******

The moment held two facets in his mind.

The sound of lawns cut late in the evening

and the memory of a push-up regimen he had abandoned.

It was Halloween.

An alumni newsletter lay on the hall table

but he would not/could not read it,

for his hands were the same emotional structures

in 1987 as they had been in 1942.

Nothing had changed. He had retained his tendency

to fall in love with supporting actresses

renowned for their near miss with beauty

and coffee still caused the toy ideas

he used to try out on the morning carpools,

a sweeping reorganization of the company softball league,

or how to remove algae from the windows of a houseboat.

He remembered a morning when the carpool

had been discussing how they'd like to die

The best way to go.

He said, why are you talking about this.

Just because everyone has died so far,

doesn't mean that we're going to die.

But he had waited too long to speak.

They were already in the parking garage.

And now two of them had passed away.

It was Halloween.

Another Pennsylvania sunset

backed down the local mountain

spraying the colors of a streetfighter's face

onto the narrative wallpaper of a boy's bedroom.

Once he thought all he would ever need

was a house with time and circumstance.

He slowly made his way into the kitchen

and filled a bowl with apples and raisins.

The clock was learning to be 6:34.

The willows bent to within decimals of the lawn.

It was Halloween.

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY EDITH ZIMMERMAN

But if you really hate subscriptions but love what we do, you can throw us $20 without all the extra emails to read. You’re the best. Thanks for your kindness and support!

I can't believe there are no comments here. Great essay. I was so stoked to see the name of my favorite musician attached to one of my favorite newsletters. I too gain strength from Berman's words. I think a lot of people do. There's a letter he wrote to a fan about recovery and what it requires. He was a very generous guy. There's a (controversial) article about the last days of his life that I won't link here, but in it, someone he's hanging out with says they are heading to a meeting and Berman is quoted as saying "carry the message." I think of that often. Anyway, I love him and all his work so much. Thanks for this. P.S. He did keep a blog: https://mentholmountains.blogspot.com/

David ‘s voice was in my ear for the hardest drinking and using days of my life. Then I got sober too. I loved him so and hate we lost him.