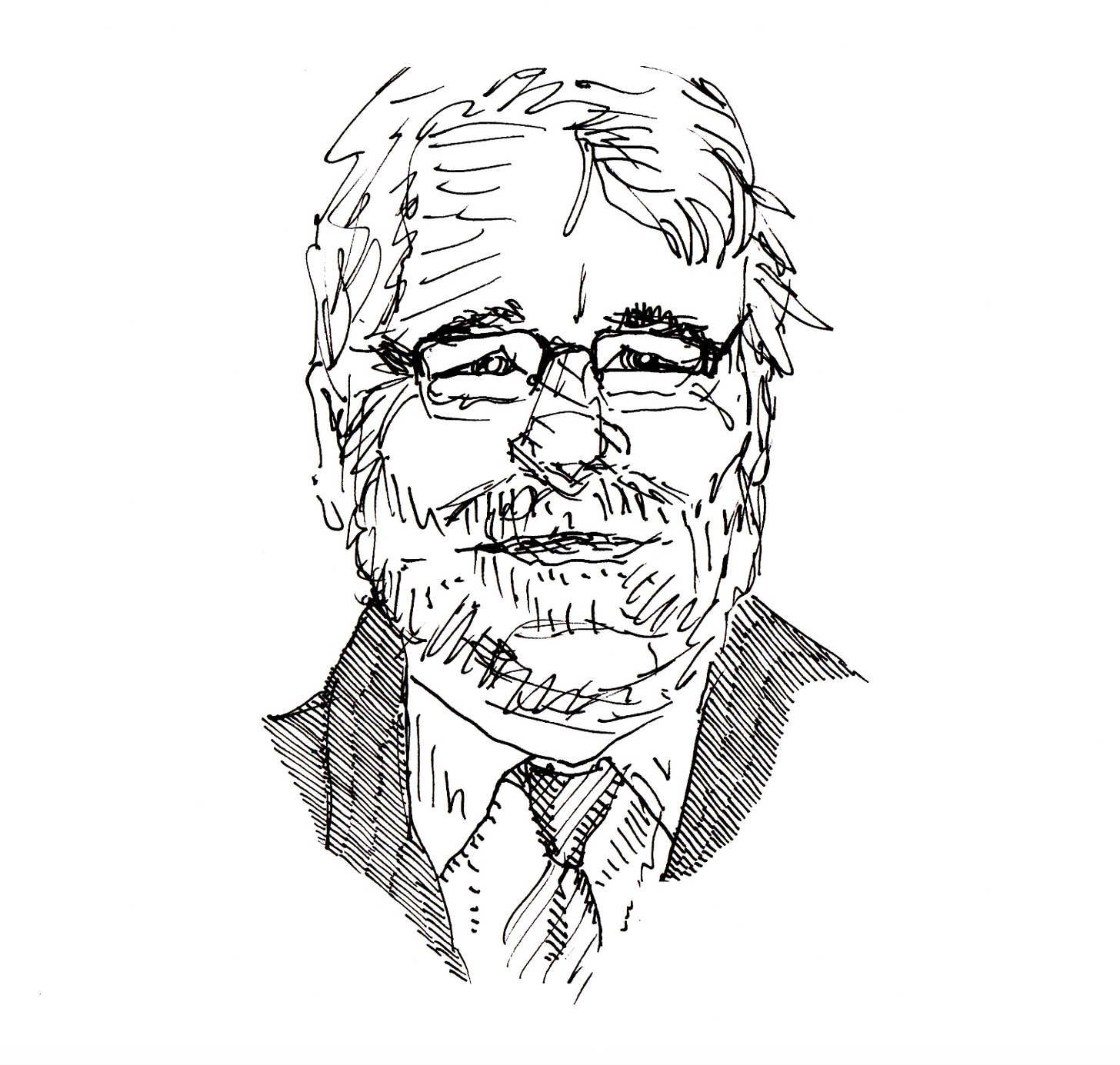

Interview with a 64-Year-Old Sober Person: Nick Flynn

"For a little while it felt like I had figured it out, how to be both sober and to be fucked up. "

TSB is funded entirely by paying subscribers. We use your money to help pay our freelancers and for Edith’s artwork. If any of our newsletters over the past year have made you feel less crappy, please consider signing up. Subscribers get access to the entire archive, the Sunday roundup of book and recovery recommendations, and the complete rundown of my weekly recovery program. Seriously—thanks for helping us.

Welcome to the last Tuesday before we descend into full-blown holiday disorder, a time of the year when many of the lonely-hearted who congregate with us each week can become overwhelmed by perverse nostalgia, longing for the safe confines of childhood, but only if their childhoods were, in fact, safe. Shit.

But we shall get through it — bravely and without escapism. Let us pray.

TSB readers know that on the third Tuesday of each month we collaborate with Oldster Magazine for the Sober Oldster Questionnaire. Welcome all who are new, and welcome back all who are old.

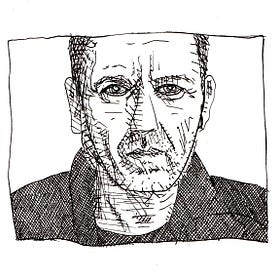

This month’s interviewee is poet, playwright, and ambassador of Suck City, Nick Flynn.

“I think we all have a shadow self, that stays with us, that makes us who we are. Some of us allow that shadow self to become our main self, and that is usually not a good thing. But I wouldn’t want my shadow self to disappear completely. I think it gives us access to some hidden realities, many of which seem to drive much of life as we know it..”

The full interview with Nick starts after the jump. This man has lived.

Thanks again to Sari Botton from Oldster for the collaboration.

How old are you, and how long have you been in recovery?

I’m 64. I walked into my first meeting in the days between Christmas and New Years in 1988. I was 28. That time of year used to be very hard for me, as it coincided with the anniversary of my mother’s suicide. (I guess you could say that time of year was hard for her as well.)

How did you get there?

I was directed into Twelve Step programs by a therapist. For the first couple years I went almost exclusively to Al-Anon. It wasn’t a good fit at first, but I was compelled to go back, mostly by desperation, but also because I saw and felt something happening in those rooms, something I hadn’t experienced before. It was a sort of wild emotional energy, which I had kept at a distance, fearing it might destroy me. The people in those rooms seemed able to ride it, somehow, and I wanted to learn how to do that.

I walked into my first meeting in the days between Christmas and New Years in 1988. I was 28. That time of year used to be very hard for me, as it coincided with the anniversary of my mother’s suicide (I guess you could say that time of year was hard for her as well).

What are the best things about being in recovery?

That changes as time passes. At first I was surprised that I would have money in my pocket at the end of each week. It was almost like magic—where did all this money come from? Then it was, as I mentioned earlier, the broadening of emotional bandwidth. At first it was a rather crude machine, full of highs and lows, but it has settled into a manageable midrange. Life was both very dramatic and very boring when I was using. Now that formula has been inverted—life is full of surprise yet free of drama.

What’s hard about being in recovery?

After ten years away, I went out for a while (“going out” is what those in recovery say when someone picks up drugs or alcohol again) and for a little while it felt like I had figured it out, how to be both sober and to be fucked up. I had missed being fucked up, even as I loved being sober. It was a paradox, a conundrum. I ran that into the ground, caused some damage, and dragged myself back into meetings. It took seven years. For the first two years when I was back my truth was that I loved to be sober and I loved to be fucked up, but that faded away. Now I can’t imagine being fucked up.

I was directed into Twelve Step programs by a therapist. For the first couple years I went almost exclusively to Al-Anon. It wasn’t a good fit at first, but I was compelled to go back, mostly by desperation, but also because I saw and felt something happening in those rooms, something I hadn’t experienced before. It was a sort of wild emotional energy, which I had kept at a distance, fearing it might destroy me. The people in those rooms seemed able to ride it, somehow, and I wanted to learn how to do that.

How has your character changed? What's better about you?

I don’t know if my character has changed. I think we all have a shadow self, that stays with us, that makes us who we are. Some of us allow that shadow self to become our main self, and that is usually not a good thing. But I wouldn’t want my shadow self to disappear completely. I think it gives us access to some hidden realities, many of which seem to drive much of life as we know it. It’s good to be aware of these forces, and not pretend they do not exist, right?

What do you still need to work on? Can you still be a monster?

I was never a monster. And there is always work to do, which simply means being open to life. I’ve been with my wife now for twenty years, we have a 16-year old daughter, we all get along. If I step back and look at that part of my life, it all seems unlikely. How did I figure that out? The same with my writing—I’m a poet, I work with language every day, I have a few books out in the world and people come up to me sometimes and tell me these poems mean something to them. It’s all a daily practice, everything, the family, the poems, the sobriety. I have spent time in a life that did not look like this, and this one seems to fit better.

What’s the best recovery memoir you’ve ever read? Tell us what you liked about it.

I always return to Kelle Groom’s I Wore the Ocean in the Shape of a Girl. Groom is a poet, and that is clear on every page. It is grounded in the muck of addiction, and yet it transforms, over and over, into these lyric passages that reveal the spirit that was always inside her.

What are some memorable sober moments?

My daughter texted me last night asking what was for dinner. She was just leaving her soccer game, which I had to sadly miss it because I was home all day working on some plumbing issues which really needed addressing—after attempting some fixes myself I had called in a plumber. When the text came in I was at a book party for my friend Susan Minot, at her apartment. At the party I got to talk with Daryl Pinkney, a writer I really admire. I didn’t look at my daughter’s text until this morning, but when I got home from the party my wife had ordered Chinese, the takeout containers were all over the counter. My wife was upset that her fortune had been “YOU WILL TRY A NEW SEAFOOD AND LIKE IT.” What the fuck? We laughed. I tried to imagine a fish no one had ever seen before. Susan’s new book is Don’t Be a Stranger. It took her eleven years to write it. I started it last night, and I already love it. Its first line is “She stayed as long as she could in the bath.”

Are you in therapy? On meds? Tell us about that.

I’ve been with a Jungian therapist for the past ten years. I write down my dreams and send them to him and we find one that is a portal into the subconscious. I used drugs and alcohol to self-medicate for a long time, but I’ve never taken doctor-prescribed meds. My depression is (was), apparently, what they call “situational” rather than a chemical imbalance. I’ve seen folks really improve with meds, but I do worry about the tendency to over-prescribe. I had anxiety for a while, an acupuncturist put a tiny needle into my earlobe, it was on a little piece of tape, and I would squeeze it whenever I felt anxious, and it would fill my head with pain, which triggered endorphins, I guess, and then eventually the anxiety subsided. A psychiatrist would have prescribed Zoloft, and I’d likely still be on it.

After ten years away, I went out for a while (“going out” is what those in recovery say when someone picks up drugs or alcohol again) and for a little while it felt like I had figured it out, how to be both sober and to be fucked up. I had missed being fucked up, even as I loved being sober. It was a paradox, a conundrum. I ran that into the ground, caused some damage, and dragged myself back into meetings. It took seven years. For the first two years when I was back my truth was that I loved to be sober and I loved to be fucked up, but that faded away. Now I can’t imagine being fucked up.

What sort of activities or groups do you participate in to help your recovery? (i.e. swimming, 12-step, meditation, et cetera)

I ride my bike around Brooklyn, I meditate some, I do yoga, I have a writing group, I got my meetings, I meet up with friends. For the past couple years I’ve tried to meet up with my wife when she goes for her afternoon coffee. I quit caffeine three years ago, but my wife still functions on it, and so we just walk to the coffee place, and talk, check in on how the day is going. It’s really simple, takes about half an hour, and it seems to have made everything better. Who knew the secret was just making time to talk to your partner?

Are there any questions we haven’t asked you that you think we should add to this? And would you like to answer it?

I think we good…thanks for doing this.

**********************************************************************

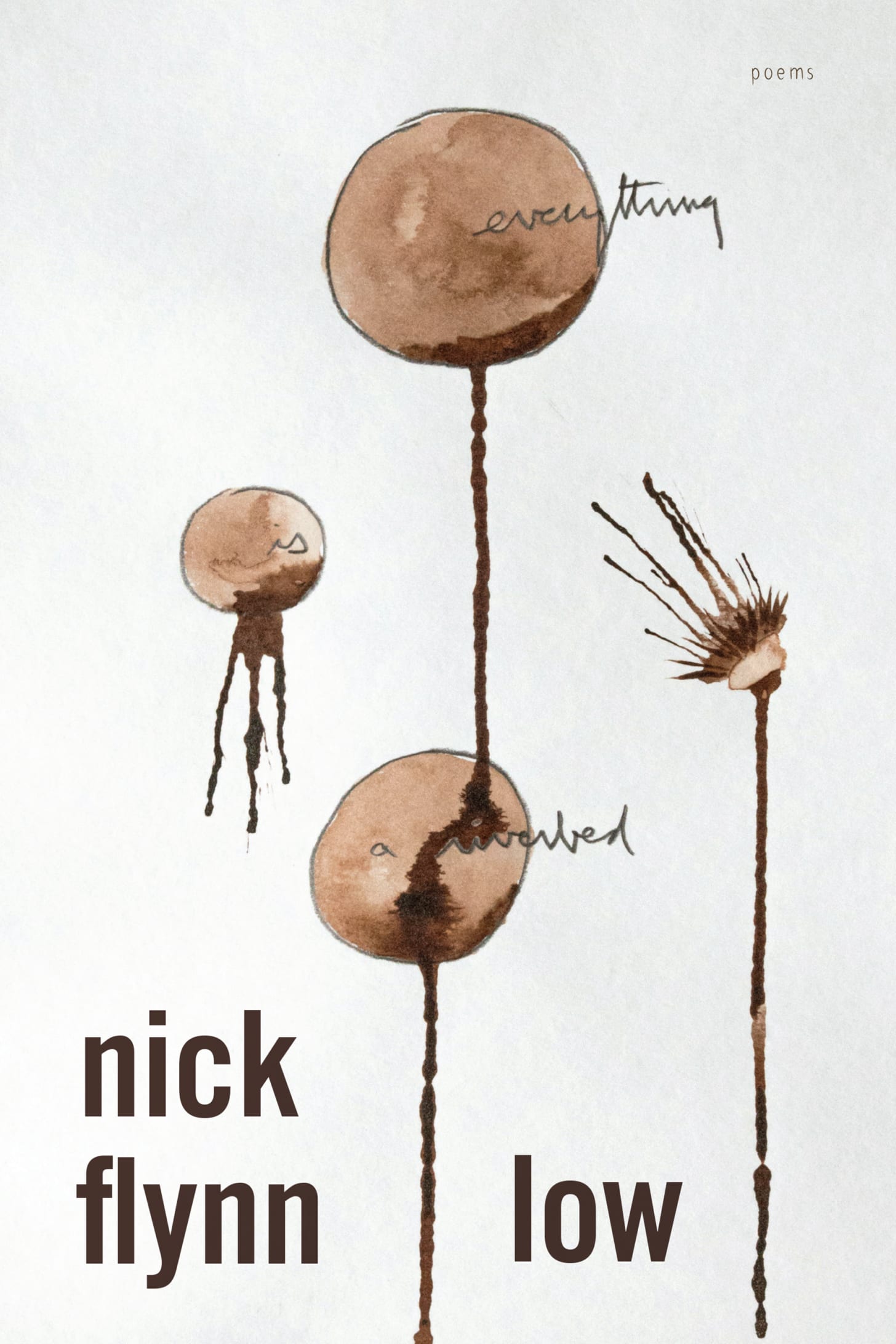

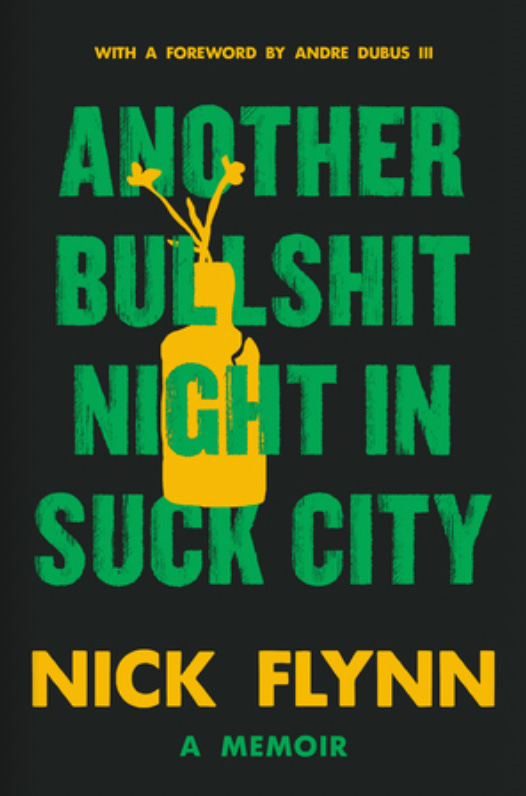

Nick Flynn (writer, playwright, and poet) is the author of thirteen books, including Low (Graywolf, 2023) and Some Ether (Graywolf, 2000), winner of the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award. His bestselling memoir Another Bullshit Night in Suck City (Norton, 2004) was made into a film starring Robert DeNiro (Focus Features, 2012) and has been translated into fifteen languages. Stay: Threads, Collaborations, and Conversations (Ze Books, 2020), documents twenty-five years of his collaborations with artists, filmmakers, and composers.

******

This monthly interview series is a collaboration between Oldster Magazine and The Small Bow,

MORE IN THIS SERIES:

Interview with a 54-Year-Old Sober Person: Kristi Coulter

Interview with a 53-Year-Old Sober Person: Joan As Police Woman

Interview with a 60-Year-Old Sober Person: Claudia Lonow

*****

*****

This is The Small Bow newsletter. It is mostly written and edited by A.J. Daulerio. And Edith Zimmerman always illustrates it. We need your support to keep going and growing.

We send it out every Tuesday and Friday. For $8 a month or $60 per year, you also get a Sunday issue and access to the full TSB archives.

Oh, do you like coffee mugs? We also have some amazing TSB merchandise for sale.

If you'd like to check in with me and learn more about our recovery meetings, here's where I can be reached: ajd@thesmallbow.com

Also, follow us on Instagram for updates and more illustrations from Edith.

ZOOM MEETING SCHEDULE

Monday: 5:30 p.m. PT/8:30 ET

Wednesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Thursday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET (Women and non-binary meeting.)

Friday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Saturday: Mental Health Focus (Peer support for bipolar/anxiety/depression) 9:30 a.m. PT/12:30 p.m. ET

Sunday: (Mental Health and Sobriety Support Group.) 1:00 p.m PT/4 p.m. ET

*****

If you don't feel comfortable calling yourself an "alcoholic," that's fine. If you have issues with sex, food, drugs, codependency, love, loneliness, and/or depression, come on in. Newcomers are especially welcome.

FORMAT: CROSSTALK, TOPIC MEETING

We're there for an hour, sometimes more. We'd love to have you.

Meeting ID: 874 2568 6609

PASSWORD TO ZOOM: nickfoles

Need more info?: ajd@thesmallbow.com

A POEM ON THE WAY OUT:

Philip Seymour Hoffman

by Nick Flynn

**************************

Last summer I found a small box stashed away in my apartment,

a box filled with enough Vicodin to kill me. I would have sworn

that I'd thrown it away years earlier, but apparently not. I stared

at the white pills blankly for a long while, I even took a picture of

them, before (finally, definitely) throwing them away. I'd been

sober (again) for some years when I found that box, but every

addict has one— a little box, metaphorical or actual— hidden

away. Before I flushed them I held them in my palm, marveling

that at some point in the not-so-distant past it seemed a good

idea to keep a stash of pills on hand. For an emergency, I told

myself. What kind of emergency? What if I needed a root canal

on a Sunday night? This little box would see me through until

the dentist showed up for work the next morning. Half my

brain told me that, while the other half knew that looking into

that box was akin to seeing a photograph of myself standing on

the edge of a bridge, a bridge in the familiar dark neighborhood

of my mind, that comfortable place where I could somehow

believe that fuck it was an adequate response to life.

— from Poetry Foundation

But if you really want to avoid the in-box clutter, feel free to donate $25 or more by pressing this button. This helps us pay for the production costs for the TSB Pod.

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY EDITH ZIMMERMAN